|

Author of the Month Charles McCain [September 2009] Chosen by MyShelf.Com reviewer and Babes to Teens Columnist Beverly Rowe |

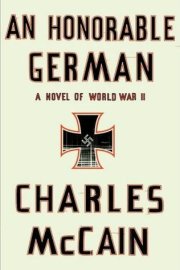

In his debut novel,

An

Honorable German, Charles McCain tells the epic story of a heroic and conflicted

German U-Boat commander. His research is impeccable, and the story feels realistic enough

to put you right in the action; but he tells us the story of the German families at home too,

and the unbelievable trauma of being attacked by the Allies.

In his debut novel,

An

Honorable German, Charles McCain tells the epic story of a heroic and conflicted

German U-Boat commander. His research is impeccable, and the story feels realistic enough

to put you right in the action; but he tells us the story of the German families at home too,

and the unbelievable trauma of being attacked by the Allies.

I've read quite a few World War II books, both fiction and nonfiction, but this was the first book I had read from the German viewpoint about World War II, and one of the best historical novels I have ever read.

Charles Mc Cain is an incredible author who is passionate about his subject. He's an exciting man who builds that passion and excitement into his work. I can definitely see An Honorable German as a blockbuster movie. It's an unforgettable story by an author we want to see more of.

I asked Charles if he would answer some questions for us at MyShelf.com....here is what he had to say.

Bev: I really did enjoy reading An Honorable German. Looking at World War II from the viewpoint of a German Naval officer was a rare experience. I can not even imagine the work that went into writing that novel.

Charles: Thank you! Sometimes I canít imagine it myself. Fortunately, I like to read, and reading about WWII and the Third Reich is something Iíve done since I was a young teenager. Even those years when I wasnít thinking about the novel I was always reading. My publisher thinks I may be the only American author, if not the only author, ever to write a WWII epic from the German point of view. (Given the research I can certainly understand why).

The inspiration for the novel began with an article in a 1944 edition of Time magazine I picked up in the Tulane University library, while pretending to study for final exams. This article recounted how a number of German Navy prisoners had tunneled out of a POW camp in Phoenix, AZ and temporarily escaped. I had no idea there were German POWs in the US in WW Two. (There were 375,000). And I was very surprised that some of these prisoners—approximately 8,000—were from the U-boat force, or Ubootwaffe as the Germans call it.

I initially wanted to write the German version of The Great Escape (

book

| movie).

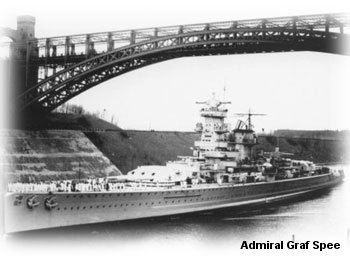

But my story first had to get the men to the POW camp. Several Germans named in the Time

article had been aboard the pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee,

including the leader of the escape, who had been

the Senior Navigation Officer. I later corresponded with him. These men from the Graf Spee

had escaped from Argentina in 1940 and made their way back to Germany, then to be pressed into

service on U-Boats, from which they were ultimately captured. I discovered all of this through

my research. The journey of these men from the Graf Spee to U-Boats to captivity in a POW

camp in Arizona fascinated me.

including the leader of the escape, who had been

the Senior Navigation Officer. I later corresponded with him. These men from the Graf Spee

had escaped from Argentina in 1940 and made their way back to Germany, then to be pressed into

service on U-Boats, from which they were ultimately captured. I discovered all of this through

my research. The journey of these men from the Graf Spee to U-Boats to captivity in a POW

camp in Arizona fascinated me.

When I plotted these events out over time, and wrote and rewrote different sections of the novel, it finally became clear that the journey of the protagonist to the POW camp was the most interesting and longest part of the story line. But this was more an unconscious process at the time. Only by looking backward do I understand it.

Bev: Please tell us about yourself, your life up to now, and your road to publication.

Charles: Well thatís a lot to answer in a few paragraphs! After I had signed the contract with the publisher I told my editor that I had all three things everyone wanted in a novelist. "What are those," he asked me. "I'm from the oral tradition of the South which has produced many Southern writers, I had a traumatic childhood and Iíve suffered from depression." He was most impressed. "All three?" "Yes." We had a long laugh although it is true. I told him that most Southerners can talk the bark off a tree and thatís why so many of us become writers. We want to get away from our relatives who wonít shut up.

I grew up in my motherís hometown of Orangeburg, SC. Unfortunately, my parents and my grandparents died when I was a youth and my older sister, one of two people to whom the book is dedicated, raised me from the time I was a young teenager. She is seven years older than me and we really didnít know each other very well. So imagine being 22 years old and living in Washington, DC, only to move back to South Carolina to look after a 15 year old little brother who was a complete hellion. That was our situation. The dedication in the book says it all: "With love to my older sister Mimi who many times in her life has given me the courage to go on." Sometimes people tell me I must read A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. I tell them, "I wouldnít go near that book with a barge pole."

The subtext of An Honorable German—being abandoned by people you love because they die; the fear of sudden death; and brooding over your own death, yet still going on in spite of your grief and pain—that subtext is from my own life. There are two lines in the novel that speak poignantly to this and are drawn from my own life. And they seemed even more prescient when I was diagnosed with cancer three days after I signed the final proof of the novel. Fortunately, the Almighty and the brilliant physicians at the National Cancer Institute cured me of that monster.

"It wasnít anger, or love or desire or even fear that kept him alive. It was simply his primal will to survive; an independent force within him, bound neither by logic nor reason; a force few ever discovered in themselves." An Honorable German

I graduated from Tulane University in New Orleans, which took me five years because all I wanted to do was read novels, study history and raise hell. I accomplished all of these goals, including being thrown out of the rowdiest bar in New Orleans—Pat OíBrienís.

After college I spent almost three years working full-time, researching and writing numerous drafts of the manuscript which became An Honorable German. I could not get anyone interested no matter what I did. I grew despondent and actually quit writing.

I moved to Florida and had to find a job, since my dream of being a novelist had slipped from my grasp. I didnít know much, but I did know how to take a few facts and spin a convincing story, which qualified me to become a stockbroker. I then made a professional career in the financial services industry.

Then, not three years ago, an author friend of mine read my

forgotten manuscript, which I had

not looked at in fourteen years. I had almost thrown it away. It was not in an electronic format,

and only two paper copies existed. He called his agent and said he had just read the best WWII

novel of his life. She immediately wanted to read it, but I refused. I didnít want to go back to

it. There had been so much disappointment. He hectored me. I asked him why in the hell a

literary agent in Washington, DC who probably sold nothing but "kiss and tell" memoirs would know

or care about a novel featuring a German U-Boat captain in WWII?

Then, not three years ago, an author friend of mine read my

forgotten manuscript, which I had

not looked at in fourteen years. I had almost thrown it away. It was not in an electronic format,

and only two paper copies existed. He called his agent and said he had just read the best WWII

novel of his life. She immediately wanted to read it, but I refused. I didnít want to go back to

it. There had been so much disappointment. He hectored me. I asked him why in the hell a

literary agent in Washington, DC who probably sold nothing but "kiss and tell" memoirs would know

or care about a novel featuring a German U-Boat captain in WWII?

My friend said, "She discovered Tom Clancy." Long pause. "Well, if youíll stop badgering me I guess you can take it to her." She signed me as a client. I quit my job and spent the next 18 months working full-time on the novel both before and after it was sold to Grand Central Publishers.

Bev: Were you influenced by any other authors? Who are your favorites?

Charles: When I was twelve, my mother gave me an old paperback copy of Mr. Midshipman Hornblower by C.S. Forester. From then on I was hooked. Iíve probably read the entire Hornblower series thirty times. Iíve read them again recently, and I can see the effect it had on me and my writing. Another influence at the time I wrote my original drafts was Gorky Park, by Martin Cruz Smith. Published during the Cold War, it was the first of these Soviet era murder mysteries that have become so popular. The author had done incredible research into the details of everyday life in the Soviet Union by interviewing Russians who had defected to the United States. Itís hard to believe it now, but the Soviet Union was the most ominous society in the world after the Nazis were defeated and the Cold War began. We knew little about it then, and I was fascinated with the details of everyday life and how that gave verisimilitude to the story. In An Honorable German, I very much wanted to give readers a sense of everyday life in another ominous society, the Third Reich. You have to paint the details in very carefully—like watercolors on an eggshell—because you never want the history to be obvious, or to overwhelm the protagonist, since the book is about him. The protagonist always needs to be center stage and you have to color in the backdrop very carefully lest it be too bright.

Three other writers who influenced me are Hemingway, Evelyn Waugh and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Hemingway because he is the best writer of the "American" language. Blunt. To the point. All the useless decorative words shorn off. Evelyn Waugh because he is the best stylist of the English language in the 20th century. He writes so beautifully that sometimes I cry when I read sections of Brideshead Revisited or his Sword of Honor Trilogy. And Fitzgerald because of the impact The Great Gatsby had on me when I was struggling to master the rudiments of novel writing. I distinctly remember reading it in 1981 and telling myself that if I could only write one sentence as wonderful and haunting and perfect as he did thousands of times, then it would be worth all the work. And no, I still havenít done it.

Bev: Max is a very compelling character. Is he based on any real person? Tell us about the development of this character and others in the novel.

Charles: A part of him is based on me, which is very hard to avoid since one knows oneself the best. This also reveals oneself in conscious and unconscious ways, which I donít want to do. Since I wrote the first drafts of the novel when I was 22, Max in many ways represents the kind of man I wanted to be, with the kind of father I had wanted, and the kind of courage I needed and wanted to live my life. The majority of Max, however, is a figment of my imagination, although he seems very, very real to me.

Bev: The Naval battles seemed so realistic and frightening. Tell us about your research for that phase of your story.

Charles: I have read about practically every naval battle that ever happened, including all the books on the Graf Spee, at least 50 books on U-boats, and countless memoirs of life at sea, battles at sea and bad weather at sea from the Age of Sail to the present day. I have also read dozens of memoirs of soldiers who have been in battle and all of them comment on how unreal it seems—dream-like almost—and how long combat seems to go on, yet afterward one realizes it was just a short time. I combine all that with my imagination.

As a historical novelist, you have to learn the original story so well that you can write it by memory, and paint your characters into the actual history without changing it. And finally, 35 years ago, my writing mentor said something to me which I have always practiced: "If the action is not happening to someone, itís not happening." Throughout the book I constantly keep in mind and describe to readers what Max smells, what he sees, hears, feels. But it has to be judicious because you donít want to describe all things at one time.

Bev: Your descriptions of the bombing of Berlin were also realistic, and very emotional. How did you psyche yourself up to write these scenes?

Charles: My shrink told me something interesting about those scenes. He told me writers are able to access that part of the unconscious which contains the roiling witchís brew of our most powerful and frightening emotions: fear, lust, greed, hatred, love, envy. But unlike other people, writers can access that part of themselves without freaking out, so a writer can draw on that part of himself to describe, say, the horror of being bombed, then put the lid back on and go out for coffee.

Itís also important to remember that Iíve read dozens of books on the Anglo-American bombing offensive against Germany (with which I personally fully agree) and so it isnít gut wrenching to write about, since I had read so much about them, and I rewrote those scenes at least a dozen times. Because of that, the horror loses its impact. There is a paragraph in one of the bombing scenes that contains a phrase, "fire so terrible, fire so merciless that all you could do was run from it with all the strength God had given you." And I remember writing that and thinking to myself, "Wow, that totally captures the mood."

Bev: We Americans tend to think of all the Germans that were involved with "The good War" as being Nazis. Of course, as your book really points out, they were not. Do you get any criticism for writing this story with a German Officer as the good guy?

Charles: Fortunately not because I wondered about that before the book was published. I personally despise Nazism, and politically, Iím a yellow dog Democrat as we used to say in the South. (Iíd vote for a Ďyellow dogí before I would vote Republican). But Iíve learned that readers know there is a difference between the novel and the novelist. That people find the story so convincing is a testament to my skill as a novelist. It doesnít mean I agree with everything in it. I despise the Third Reich.

Bev: I had previously read about German sailors from the U505 in Gary Moore's nonfiction Playing with the Enemy ( reviewed at Myshelf) who were incarcerated in an American prison camp, and now you are telling us about another prison camp in Arizona. I don't believe that most Americans knew about prisoners of war being held within the US. Tell us about that.

Charles: I havenít read Playing With the Enemy but reading your review I plan to. The U-505 story was one of the great secrets of the war and is the only ship captured on the high seas by the US Navy since the War of 1812. The U-Boat itself is beautifully preserved in its original condition at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

But to your questions on POWs. When I read the Time magazine article which gave me the idea for the novel, what astounded me most was learning that there were German POWs in the US. What astounded me even further during my research was when I learned there were almost 400,000 German POWs, including the entire Afrika Korps. (We also imprisoned a number of Germans who were American citizens for the same specious reasons we imprisoned Japanese-Americans). I have discovered over time that people who grew up in small agricultural towns, where there had been German POWs did know about this, since it had happened within the living memory of some people in the town.

During my research, I reviewed documents from the archives of the Provost Marshal General of the US Army, which had custody of all POWs, and discovered there were camps in every single state of the union. (Alaska and Hawaii were not states at that time and had no POW camps). Because so many of our young men were overseas fighting there was a huge demand for labor and most of the German prisoners were happy to work, since they were paid.

Under the Geneva Convention of the time, enlisted men who were prisoners of war could be forced to work but officers could not, although they could volunteer to work. So German POWs provided a large amount of farm labor. Many had grown up on farms and knew the job, and along with their guards, they ate with the farm families just like other hired hands. There are unsubstantiated stories that German POWs in states like Nebraska and Minnesota, with large German populations, often worked on farms owned by their American relatives.

Other POWs did such things as repair US Army vehicles, and to the surprise and dismay and often anger of American soldiers, German POWs processed many of our soldiers coming back from Europe where they had been fighting the Germans.

Several Americans did assist German POWs in escaping, although none of the POWs got very far. Some of the American citizens who helped in these escape attempts were tried and executed.

Bev: What was your biggest challenge in writing this novel?

Charles: First, teaching myself how to write a novel. Second, ensuring the novel gave the illusion of being German. Since it is written in English, for an English-speaking audience, it canít actually be too German in feeling or people wonít identify with it. I had to create the illusion it was German and also have the words and dialect reflect the era of the late 1930s and early 1940s.

This meant stamping out all Americanisms. Iíd use either archaic or British spellings of words such as aeroplane, and characters in the novel never phoned each other, they telephoned—or rang—each other. They didnít drive cars, they drove automobiles or motorcars. I also researched German idioms and talked to German friends and used as many idioms as I could where their context would explain them. For example, their phrase for "paper pushers" or bureaucrats, is "office horses" which I use because the context explains it.

Bev: What was your favorite part of the book, and why?

Charles: Well an author likes all of his work, but if I had to choose I would say that one of the U-Boat chapters and one of the bombing chapter are my favorites.

Bev: Your least favorite and why?

Charles: I canít say I have a least favorite. If something wasnít appealing to me, I cut it out. To me, when writing a novel, the most important audience is the novelist. If I donít like something, I cut it out.

Bev: You mentioned in your online bio that you had written two other novels before this one. Do you have plans to publish either or both of them?

Charles: I wrote a novel in college which I threw away. I wrote halves of three novels after that which I also discarded, and I wrote one novel after An Honorable German. It is titled Vote Early and Often and is a first person coming of age story set during a political campaign in New Orleans. I had been very involved in politics in New Orleans, which was quite an experience. The novel is autobiographical but I would have to rewrite it to make it viable, and that would be emotionally painful to do. I doubt I will try and get it published, at least not right now. Besides, publishers donít want you to write outside your genre because that screws up your "brand." If you can write lots of different novels about different subjects, told from third person to first person—this isnít actually useful.

I have lots of other things Iíve written—most of them about the South—and Iíve thought about writing a reminiscence about growing up in the small town in the South where my family had lived since before the Civil War. I want to call it In The Shade of the Trees—thought to be the dying words of Stonewall Jackson, who purportedly said, "Let us cross over the river and rest in the shade of the trees." (As with many famous quotes of the Civil War, it was likely invented by a newspaper reporter). But writing something like that would also be very difficult for me emotionally, and I may not be able to do it.

Bev: What are you working on now? Do you have plans for future novels?

Charles: Iím working on a proposal for another WWII novel featuring a German naval officer, but this time a completely different character. I would like to use this character in a series of novels. My editor told me that by being the first American author to write a high concept action/adventure novel from the German point of view, I had invented my own sub genre. So Iíll stick with it. At the same time there are so many other things I want to write. So who knows?

One of my lifelong dreams has been to get An Honorable German published. (The original title was Sea Eagle).I temporarily quit working in the business world to put all my energy into rewriting and polishing this novel. But I donít make enough money from novels to write full-time so I will return to the business world shortly. Novel writing will again become an avocation as it was before An Honorable German.

Bev: Do you have any other thoughts you would like to share with fans?

Charles: People often say to me that they wish they could write. And I tell them they can. They may not have the talent to write a novel or a play or a short story, but they do have the skill to write. In this day and time where email abounds and you can send a birthday card electronically, nothing touches people so much as receiving a hand-written note or letter wishing them a happy birthday, or condolences or congratulations.

It doesnít matter if the prose isnít smooth and you misspell words. What is important is that you took the time to sit down and think about that person and then write something to send them—about something funny you shared, or how often you think of them.

My best writing will never be published because it wasnít written to be published. A year ago I wrote a letter of condolence to an old family friend on the death of her husband, which turned into a 7,000 word reminiscence of everything I recalled about their family and mine, whose friendship goes back more than 50 years. This letter was a gift to my friend that money could not buy, and it demonstrated how much I cared. A few weeks after I sent her the letter, I received a note from her that said never in her life had she been so moved by a piece of writing, and she laughed and cried as she read through it repeatedly. What more could a writer ask for than that? I will treasure her letter always.

And so I tell everyone, if you can walk into a drug store to buy a card—buy a pad of paper instead—it can be notebook paper or lined school childrenís paper—it doesnít matter. Then go home and write to the person you were going to send the card to. Make up a bad poem. Anything. And your friend or loved one will cherish that piece of writing more than anything else they received. Try it.

Bev: Charles, thank you so much for sharing your thoughts with us at MyShelf.com. An Honorable German is certainly one of the best books I've read and I will be watching for your next book...you have me hooked.

Reviews:

Read Bev's reviews for Myshelf of

Websites: An FAQ about An Honorable German can be found on the author's website at

2009's Honorary List

| Jessica Burkhart | |||||